I have dedicated my life, so far, to dance and performance. I launched myself in and have not been off this course since I was 12 years old. I met my primary collaborator, and future husband, Mark Coniglio while we were students at California Institute of the Arts in the mid-1980s. He and I began an intense collaboration focusing on the integration of dance and technology and creating large-scale performance works. We co-founded our performance ensemble Troika Ranch in 1994. In 1999 we instituted an annual workshop in New York City to teach performing artists how to create media intensive works for the stage. That far-reaching educational platform super-charged our influence on the evolution of how digital technology would be used in live performance. As Troika Ranch, Mark and I have made nine evening-length works and several smaller works and works for students. Mark is the inventor of MidiDancer (1989), a body costume embedded with sensors that measure the flexion and extension of the major joints of the body and uses that data to wirelessly manipulate media materials in real-time. He later created Isadora (1999), an award winning user-friendly media manipulation software. I am one of an elite class of choreographers who have choreographed exclusively with these specialized technologies, engaging in two decades of vigorous physical research and contributing to the development of these, and other media-performance tools. As pioneers in the field of Dance & Technology Mark, Troika Ranch and I and have been written about in books, journals and other publications on live-media collaboration, as well as been the subjects of many MFA and PhD theses. We directed Troika Ranch together as artistic and romantic partners in New York City for fifteen years.

And then, at age 41, the life that I had been building and thought would continue to build, collapsed as Mark and I divorced. I collapsed with it but after a recovery period decided it was time to rebuild. One of the reasons I chose graduate school was because I had some very serious questions about whether I wanted to continue dedicating my life to dance and performance. To find out, I needed first to reconnect with the field. Being the choreographer and director of a busy, touring performance ensemble had not allowed me much time to reflect. I had been in output mode creating and presenting performances for my company and for students; developing teaching methodologies and teaching workshops; being interviewed and writing grants and writing articles, etc. I had been mired in my personal artistic interests within Troika Ranch, the outcome of which is my principle artistic identity. At 45, unmarried, uprooted and uncertain about what my next artistic trajectory might be, I chose to go back to school. Graduate school provides a supportive safe haven of opportunity to look around at what others in the field are doing; to read books on past and present art movements; to reacquaint myself with my original inspirations; to find out if I am still doing what I want to be doing; and to find out what I might do as a solo artist.

All of my graduate research manifests from my experience during the making of my last major work for Troika Ranch, loopdiver. Supported by a two-year grant from the Doris Duke Foundation and commission from the Lied Center for Performing Arts, loopdiver began in 2007 and premiered in 2009, the exact duration of the shift in my personal life from separation through divorce from my primary artistic collaborator, and thus leaving a feeling of personal devastation associated with that work. The choreography was unusually difficult to make, to learn and to practice. Created from a video-based visual score of looped movement material, intense memorization and physical rigor were required. It was the most expensive work Troika Ranch has made to date, which includes a cast and crew of eleven people and the shipping and storage of a 1800 pound complicated set, and the piece was intimate by design with audience located very close up on both sides of stage. Some of my current research is a continuation of the process used in making loopdiver and some is a departure.

I have been consistent in my investigative process over the course of the past three semesters. During this time period all of my work has been about using what is close at hand, investigating my real life in the real moment of performing and not pretending that we are not in a performance together, engaging my audience as real people right there, not letting the space go unnoticed or unaddressed, and using improvisation and visual scores to generate choreography. And, for the most part, performed as solos by me.

The research begins with the reality of my actual life. Being in mid-life, feeling how my life has changed since I moved away from New York City and relocated to Portland, OR and the impact that my life collapse had on my art-making process have all lead me to question why I make performance and what I think it was, is and could be. My overarching personal question has been how my art making can fit as a facet of my life rather than the total focus of my life. As part of my personal redefinition I have decided to eliminate the term dance as a descriptor of what I do as a solo artist.My paper What to Call it and Why discusses why I think this matters, or doesn’t.

The site/environment that I continuously investigated through various class studies has been the very personal space of my home. This choice came first from necessity; I needed a cheap, available space in which to explore the relationship of site/environment and performance. Then, as I looked at the studies I had done in this site – my house, my back porch, my yard, my garage – I began to see that the examination of my personal in relation to my artistic held a beautiful metaphoric resonance with home as performance site. Moving performance site from house to garage was first also one of practicality – I needed a slightly larger, dry (it rains a lot in Portland), convenient space and there it was. But the moment I stepped into the garage as performance space, it became an important overarching theme; a garage is a place where things get worked on and since I am working on myself as an artist, and art making is work, it felt wholly appropriate. In addition, the romanticism of the garage as a place where great ideas are born was irresistible. Making performance for space other than traditional theater space had gotten me thinking about what a “site” really is. If a site is a space that impacts the creation and/or design of the event happening within it, then every performance might be considered “site specific”. It then comes down to a matter of degree of impact. Traditional theaters come with conditions and constraints but many artists prefer to transform the theater into some “other” space where the performance (fantasy) takes place. However, if an audience member lets their peripheral vision go, they remember that they are in a building called a theater engaging in a performance (fantasy) and, in order to return to the performance (fantasy), they must suspend their disbelief. Connecting to my interest for “realness” in performance, the garage requires no suspension of disbelief allowing me to fully acknowledge it as content. It is a garage and I want you to know that it is a garage. Research element #1: using non-traditional performance space and letting the reality of that space act on the content of the work.

Another facet to performing in my home is my interest in unearthing aspects of this special thing we engage in called “performance” that is not the performance itself but is the reality underneath the performance (fantasy). My work aims to point out that there are at least two realities going on in any performance: the reality-reality of us people gathering in a room together playing our designated roles in this thing called a performance, and the fantasy-reality of the thing being “performed”. Even when sitting in a proscenium theater, an audience is performing the role of being an audience. They adhere to those codes as determined by the space and the historical conduct agreements that have been made over time. I’ve been merging these two realities into one meta-reality for my current performances. My performances are just as much about themselves (the act of a performance) as they are infused with any subject matter (the real me right now asking real questions about life and art and how they fit together). In the words of John Cage, “I have nothing to say, and I am saying it”. My current work speaks only of itself. Research element #2: don’t pretend we are not involved in a performance when we are involved in a performance.

Though performed in a traditional theater space, an early outcome of my research is my solo this is what this is (performance segment begins at 04:45) performed in August 2012 at the culmination of the first semester of this program. I used video projections of the space itself to amplify where we were; I used video of my classmates who were (and are) the most important witnesses of my graduate school experience and who were also performing that night; I created a fixed structure for the action but the specific material was all improvised; and I address the audience from within the performance. By turning on the house lights and directly addressing the audience (commonly known as breaking the fourth wall) they became aware of themselves in the moment of performance while I was in a vulnerable and present state of improvisation.

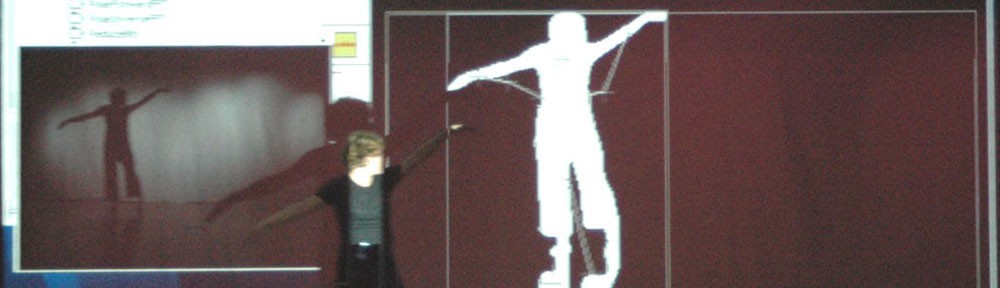

Embedded in my investigation of performance environment and performance itself is my interest in choreographic intervention, which began in loopdiver. Looping (scroll to Choreographic Process) recorded movement material through a computer process then asking humans to learn what was essentially impossible to perform was an exhilarating physical imposition that generated movement material that would never have come up without the intervention of the computer. I am attracted to intervention because I believe that limitation provides greater creativity. Intervention causes me to face difficult or impossible movement requests that I could not have conceived of and to find clever and compelling ways to deliver those requests. I am inspired by this challenge. I have continued my exploration of intervention by creating very low-tech “visual scores”, things a performer looks at to determine his or her next move. These scores are manipulated, rearranged, and composed if you will, by an audience

Being on the ground level eye-to-eye with my audience is another facet of investigating what it means to be engaged in a performance. The audience is part of the process of intervention as they are the ones who determine what action occurs and when. I have an interest in involving the audience to give them open admittance into the creative process, to activate their own creative agency, and to level the hierarchy between audience and performer. Passivity in performance holds no interest for me at this moment.

This visual-scoring and audience participation part of my research are also being used toward a new work called SWARM (see SWARM document), a performance installation informed by emergent systems, that I am making in collaboration with Mark Coniglio for our company Troika Ranch. In typical Troika Ranch fashion, SWARM will use sophisticated hardware and software to track audience behavior and use analysis of that behavior to recall and wirelessly transmit pre-recorded movement and vocal material from a computer to earphones and head mounted visual displays worn by performers; the performers do what they hear/see. The pre-determined materials are held in a databank of possibilities but the audience’s distinct behavior during each performance will generate a unique sequencing and a related but specific drama each time. The visual scoring element is connected to the direct participation of an audience. AM I CUTOUT FOR THIS was my first investigation into working with a visual score that involved audience participation. In my garage I use material images and objects that audience members can physically manipulate to determine performer action in real time. I am bringing the audience in on ground level, giving them a role and keeping them close by. I am observing how much information an audience needs to understand the relationship of their action to performer action; how comfortable are they to participate and what causes the level of comfort, and what happens to the dramatic content when it is shuffled around by the differing choices of audience members from performance to performance. Research element #3: Choreographic intervention by audience participation: visual-scores manipulated, rearranged, composed directly by audience.

Encapsulating all of my research is my present embrace of “low-impact” art. I have written a few papers recently that confront and question the problems of subsidy, visibility and inclusion in the art world. Administering your own work as an artist is exhausting and distracting from the act of making the work itself so I chose to eliminate that part for now. By “low-impact” I am referring to the lack of impact on me, the creator. In this process there is no money, no presenters, no press, and no “next”, meaning the performance is not about getting me to the next gig but only to the next idea. What is in place of the noes are yeses to playful exploration, rigorous experimentation, happy accidents and meaningful mistakes. After loopdiver, which was so rigid and organized, I wanted to lose some control over everything, not know the answer and make a bit of a mess. I wanted a very low-pressure situation under which to conduct the public expression of my research in these early stages. The outgrowth of this thinking is Salon du Garage, the series of performance experiments that I began in December 2012, recommenced every weekend in April 2013 and will continue in May 2013 with the inclusion of special guests. It is highly probable that my thesis concert will take place in my garage. It has become the perfect setting for my artistic inquiries while also holding a kind of intrigue for audiences.

I love the garage because of its grunginess, because it can only hold so many people, and because it implies something “being worked on”. What better place for me to be working on my craft, and by extension, myself. The garage is messy and intimate and full of poetic potential. It provides me with a safe, unconventional, total-immersion arena that I can fully occupy and, since I own it, is not financially risky. I don’t have to rely on ticket sales or fundraising to make this work happen. While these choices were instigated out of necessity, choosing “low impact” has a question within, “is my performance still valid as “high-art” when it is something I engage in on the weekends in my garage?” Who decides what is successful and what is not if I choose not to participate in the art-world structures that usually determine this? I am finding out that it is the audience and me who feel successful and validated each Saturday. Salon du Garage has become the site for my collective research, all the elements rolled into one. The process IS the performance: we are engaged in a real thing called performance (fantasy), in a garage, you are part of it and it’s free. Research element #4: making art without subsidy/support; removing the pressure of the business of art; art as part of normal everyday life.

There has just been one article written about my work during the time I have been in graduate school, which ironically enough, is an article from The Washington Post. While initially instigated by a query about what is happening with digital technology and dance in general, the interview quickly diverted to some of the research processes I have been engaging in for SWARM in the garage. The entire Sunday Arts section of the paper on March 17th was dedicated to how technology is being used across artistic métiers with the Troika Ranch coverage taking an entire page including a prominent photo. I was very pleased.

After nine months in the program my transformation as a holistic artist is evident. These awakenings are visible in my current output as performer, creator and educator. As a creator, I once again touched the initial inspirations of my journey into this field and heard my own solo voice, loud and clear, making decisions about approach, content and design. Early in the first semester I realized that my aesthetic has been highly influenced by the Surrealists. The use of collage, stream of consciousness and juxtaposition in my work comes directly from them. The Dada movement is secondarily influential in its anti-bourgeois attitude and rejections of the prevailing standards in art in the early 20th Century. A more recent influence on my current creative process is the teachings of Susan Rethorst, who is a celebrated choreographer and also a personal friend. In her book A Choreographic Mind: Autobiographical Writings, Sue makes the case that choreographers possess a “choreographic mind” meaning that there is a kinetic logic (and other logic) in the act of making movement that needs to be trusted and honored and not necessarily talked about, analyzed or justified. She writes about “making as thinking”, letting the wisdom of the body moving in time and space be an important guide that you listen to with your body and respond to by continuing to move your body. I have been following that belief wholeheartedly during this research process. Improvising forces me to rely on my physical intuition and to follow my gut in the moment. It puts my choreographic mind to work right in front of the audience. It keeps the process real for me right now. Sue writes, “I don’t want to make a dance about something, I want to make a dance that is something”. This statement comprises the totality of my current explorations.

Defining a personal teaching philosophy through pedagogy class has helped me to clarify the undercurrent of why movement as an expressive form is so important to me. As an educator in general I have been reminded to do more listening then talking, to articulate direction clearly and modify when necessary, to keenly observe the students in the room, to use improvisation early and often, to be generous with my knowledge and to let the knowledge of others come through, to speak to my students with respect and professionalism, and last but not least, to refresh the content of the workshop that I have taught annually for the past 12 years. After taking a one-year hiatus Troika Ranch will again offer its Live-I Workshop, an intensive laboratory for artists who wish to explore the creation of media intensive performances for the stage. But this year’s workshop, called The Machine Is Not Special, is expressly designed for physical performers – anyone whose primary expressive means is through the action of the body. Our idea is to use computer technology and algorithmic thinking to inspire new ways of devising and organizing movement (choreographic intervention), a network of digital constraints within to become a whirling dervish. I am once again excited to teach this workshop. Troika Ranch’s Live-I Workshop has always been taught from the perspective of the creative practice Mark and I are invested in at that moment. This year will be no different.

Through the processes and research I have engaged in during graduate school, I have been reminded that the act of making art is, in and of itself, a radical act. Independent thought is always radical. Showing up is brave. My solo work represents my personal bravery right now. It takes a stand. It is a yell. It is a shedding. It is an offering. It is the unknown. It is joy. It is fear. It is a beginning. Again.