Graduate School – GWU 4/29/2013

In 2013 audiences are involved in aspects of performance that exceed the role of observers. My interest in these various roles stems from my own making and presenting of performance work. Today I am closely examining ways in which participation in performances in the 21st century differs from previous decades. My investigation is not worldwide but instead springs from my firsthand perspective and experience as a middle-aged, mid-career, middle-class, white, American, female performing artist. While maintaining a more “traditional[1]” approach with my company Troika Ranch[2] I am also exploring strategies to make and present work as a solo artist that reconfigures audience participation.

Through research and reflection, I realize that aspects of audiences’ roles have evolved over time. What has shifted for me is my personal awareness of –and investment in — the role of my audiences. Artists are often asked, “Who is your audience?” I have added to this inquiry, “What do I want from my audience and what do they want from me?” As I explore responses to these questions, I am investigating both who and what is an audience. In other words, what is this magical, mystical body of people that performing artists rely on? This paper describes four broad categories of audience participation: audience as performer/creator, funder, public relations, and critic. Drawing from this research I explore how my current project, Salon du Garage, incorporates different aspects of these roles and why I find this shifting of traditional modes for presenting dance and performance to be both informative and inspiring.

What is an Audience?

At its most basic, an audience is a witness to our existence. In my own career, I have felt that an audience need only be present, and perhaps not say anything at all, for me to gain a new perspective on my work. I am able to sense the waxing and waning of an audience’s attention through an exchange of energy. Their energetic response gives me an otherwise unknowable awareness of the external perception of my performance.

Audiences also provide an objective validation system. A “thumbs up or down” from the public can encourage or discourage that artist to continue making work. Audiences in the 20th century have been treated almost as victims as in accounts of the Futurists and Dadaists[3] who intentionally double-booked theaters to generate fights amongst the audience. As they engaged in outrageous activities, they intended to rile and excite more than simply entertain. Antagonism and victimization carry on into the performance art movement of the 1970s and beyond with artists like Ron Athey[4] who purposefully put audiences at risk by spurting his own HIV+ blood in close quarters during a time of extreme angst about AIDS in America.

During the post-modern era, when many performing artists were wildly breaking down traditions in their fields, the evolution of the form itself was their priority, thereby leaving many audiences not knowing what to make of their explorations. Now in 2013, living in the screen age, an artist can reach an audience of millions with the click of a button. Most of that audience may be anonymous to the artist, but that barely seems to matter when the number of “hits” on a website or YouTube channel determines some artists’ bragging rights. Internet culture has created both broader audience-to-artist exposure and more anonymity between those bodies. It has liberated artists by offering alternatives to traditional means of making, funding, critiquing and marketing contemporary performance work even though these alternatives often require constant micro-management and reinvention of creative approaches.

Audience as Performer/Creator

Audience involvement within performance itself has a long history. We can see the breadth of this participation in 20th-century examples such as Tony and Tina’s Wedding[5], Marina Abramovic’s The Artist is Present[6], and the works of Gob Squad[7]. However, I believe that the introduction of the concept of “desktop publishing” expanded audience participation. In 1985, as I was coming of age as an artist myself, personal computers began showing up in people’s homes and dorm rooms. The SONY Handy-Cam was becoming available[8] so people who were not already trained technicians could shoot and edit videos themselves. Before the end of this decade, the Internet was publically manageable through a graphic user interface codified as the World Wide Web[9], which over the course of the next decade had folks of all sorts speeding onto the digital highway in droves. The addition of a digital and private avenue for creative expression coupled with extensive interconnectivity created a new and varied landscape for participation and creation.

By 2013 much of American society had become familiar with Flash Mobs and YouTube, mechanisms for an “amateur” to make and present something to a large audience. A movement called “crowdsourcing” is flourishing today and drawing on many people from disparate places to contribute material to a work. A relevant performance-film project that uses crowdsourcing is that of choreographer Bebe Miller and filmmaker Mitchell Rose called Globe Trot[10]. These artists incorporate audiences as performers, creators, and content and Globe Trot has the positive ramification of including anyone with interest in the communal creative process. This inclusion creates personal investment and personal connection, which might be the primary reasons why people participate in art activities[11]. Society’s acceptance of who is qualified to make art seems to be widening as the untrained amateur contributes more and more creative content.

Perhaps definitions of these terms may elucidate the current situation. Merriam-Webster defines professional and amateur as follows:

The definition of the word professional includes[12]: participating for gain or livelihood in an activity or field of endeavor often engaged in by amateurs <a professional golfer>; having a particular profession as a permanent career <a professional soldier>; engaged in by persons receiving financial return <a professional football player>.

The definition of the word amateur includes[13]: devotee, admirer; one who engages in a pursuit, study, science, or sport as a pastime rather than as a profession; one lacking in experience and competence in an art or science.

The origin of the word amateur comes from the Latin amator, lover. An amateur does something for love rather than money, as a devotee or admirer. Many artists today might be considered a combination of these two sides of a coin. They work hard to make money at their craft (professional) while continuing to do it regardless of that money (amateur) because they love it so much. One usually assumes that one is an amateur before becoming a professional but in the arts transitioning to being strictly professional often doesn’t happen. The line between amateur artist and professional artist has comingled into an aesthetic of its own.

This comingling may be aligned to the DIY movement that was accelerated by home computers and Internet connectivity and is one aspect in the rise of an audience as creator/performer. Another cause may be economics. As the popularity of “reality TV” was partly a result of the Hollywood writers’ strike of 2001[14], so might the inclusion of “non-professionals” be enticing for contemporary performing artists seeking to avoid the enormous expense of paying professionals. As with Americans’ lust for reality TV, the use of “real” people in performance is as much a commentary on our similarities as human beings, removing a sense of “us and them” while verifying Andy Warhol’s famous statement[15], it also eliminates an economic strain.

Audience as Funder

I recall my close friend Morton Subotnick[16] talking about composing contemporary music in a time before the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). I had a difficult time even imagining a time before the NEA, but looking closely at the trajectory of what is known as the “dance boom”, from roughly 1966 to 1989[17], a boom that was fostered by the NEA, I see a problematic correlation between initiation and longevity. The NEA is partly responsible for creating the ability to even be a professional in the field of dance and performance. While a huge catalyst in the support of the arts, the NEA has too small a budget for a country the size of the United States. The diminutive place that the arts hold in American culture means that not everyone wants to pay for it. The NEA costs American taxpayers 50 cents per year, while in Germany each taxpayer provides roughly $85 per year[18]. The NEA hit its budgetary peak in 1992 at just under $176 million[19]. Private foundations played a large part in picking up the slack, some of which were in place before the implementation of the NEA. However, many private foundations have become more concerned with large global issues and have minimized their contribution to arts funding[20], and only a small percentage of support for the arts comes from federal, state, and local governments [21]. One troubling fact is that the NEA budget was not able to grow at the same rate as the dance/performance field that it helped to create. Intentions were good but art requires constant subsidy. Artists, as always, have found other ways to finance their work. In comes the Internet once again.

Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and BOGO have been sprouting up since the beginning of the 00s[22]. Campaigns on these and other sites are increasing the way artists reach their goals. This added fundraising sphere is a positive addition to the greater landscape but reports from an artist colleague who has used crowdfunding reveal some of the negative ramifications. Creating and managing the request page requires a good deal of administration on the part of the artist. If the project does not meet its entire goal within the given timeframe, then the artist gets nothing. And finally, an artist can exhaust their resources quickly as people give to one project and then don’t want to keep getting solicited[23]. Crowdfunding is an excellent means of meeting immediate and temporary needs for a project but does not seem to be a successful way to build a long-lived and committed support base. The crowdfunding option has certainly created an alternative to the crushing competition artists face in applying for grants, and the dangerous results of using a personal credit card to fund your art. But has audiences’ financial investment changed anything about how the art is getting made? Are these groups of audience-funders a clearer indication of what an audience really wants? Is it pandering to the lowest common denominator or broadening participation[24]?

Closely related to “audience as funder” is audience as public relations. On each crowdfunding project page I saw something like this:

Audience as Public Relations

While I still get the occasional flyer or season brochure in the mail, most of my contemporaries rely on social media as public relations, taking full advantage of viral marketing. Viral marketing describes any strategy that encourages individuals to pass on a marketing message to others, creating the potential for exponential growth in the message’s exposure and influence[25]. The rapid take-over of this kind of marketing correlates with the transformation from analog promotion – paper press kits, printed photos, videotapes – to digital promotion primarily defined by the company website with a link to a downloadable .pdf press kit and digital photography and videography of the artists work. Troika Ranch has not printed a paper press kit or flyer or postcard since 2007 and as early adopters, we had a website up in 1994, which was unique. It seems to be the established rule now: if an artist doesn’t have a website then it feels purposefully rebellious.

While there are many people across the globe who do not have computers and are not jacked into the “inter-webs,” here in America most artists of my generation (GenX), and certainly those younger than me, depending on Internet traffic as a large part of their marketing campaigns. I get several arts-related email newsletters and announcements daily. Nearly every email and website have a banner of clickable icons that will instantly “share” the project. In the past year, a majority of my Facebook messages have shifted from personal communiqué to event invitations, most of which are in cities where I am not. Because I am being invited to an event in Japan this weekend, and I live in Portland, OR mid-week, I know this kind of marketing is a “spray and pray” campaign, meaning I was not specially targeted but just included in an entire list of “friends.” The “spray and pray” campaign used to be discouraged when sending out postcards costing several hundreds of dollars to print and send, but now this blanketing is expected and accepted. It’s nearly free to send and it’s obviously free to delete. However, the connotation of this kind of blanket marketing diminishes the personal connection between the audience/donor and the work/artist.

One positive aspect of audience as public relations is that people tend to share what they actually like meaning the amount of PR a project generates is closely linked to what people (audiences) actually want more of. What gets promoted is not reliant on the tastes of a few select media elites. This leveling of the hierarchy in promotions is echoed in my next point.

Audience as Critic

One of the earliest shifts in audience participation beyond observation is “audience as critic.” People have been writing online reviews and blogs for over a decade now[26]. In fact, when I was looking for the date on which The Village Voice fired some of its art critics, I found the answer on someone’s blog[27]. This is ironic because when the major print media began hemorrhaging art critics, and before they created websites for themselves, it was the blog-o-sphere that came to the rescue. Blogs of all sorts start appearing in the mid-1990s but an important early site for dance and performance criticism is The Dance Insider[28]. While founder Paul Ben-Itzak was instantly regarded as somewhat of a sh*t disturber, The Dance Insider was crucial for dance criticism throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. His Flash Reviews appeared on the site within 48 hours of the performance and were created in reaction to the lack of print media coverage for dance and performance. Paul Ben-Itzak “hired” dancers in any given community to review the work of other dancers. While this is more an example of peer-to-peer review, it is related to the role of audience as critic because most dancers are not “formally” trained in criticism causing some to question the validity of these reviews.

Discourse among those formally educated in performance history and criticism has its place in the development of the field, but is it necessary to discount responses from “others” as irrelevant? The public’s shift into these new roles is evidence that the old systems are breaking down as new ones emerge. Former dance critic Arlene Croce creates an argument for maintaining what she identified as “formal criticism” in her 1994 piece for The New Yorker: Discussing the Undiscussable[29]. Another member of the old guard, Michael Kaiser, president of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, more recently offered us his disappointment[30] with the death of formalism in critique. The emancipation of art criticism from the exclusively trained “professionals,” and its subsequent opening up to the proletariat mass of “amateurs,” is another example of a shift in access and validation.

Culturebot, a vital website for critical conversation that launched in 2009, organized a conference called, Everyone’s a Critic[31] held at On The Boards in Seattle, WA in March 2013 where Culturebot founder Andy Horwitz announced his movement called Culturebot’s Citizen Critic Project. Allowing the public to critique work levels the field between the “understander’s” and the “non-understander’s”; many contemporary performing artists have been confronted by the invited guest who responds “I don’t want to go to your show because I won’t understand it.” My response to this comment is, “Bullocks!” Encouraging “regular folks,” those not trained in dance and performance history, to attend and understand on their own terms, and to comment publically, is of utmost importance if the field wants to continue to have an audience. The grumbling from an old guard that critique by the masses will mean that the lowest common denominator will be the arbiter of “great art” exposes the misconception that there is unanimity among “formal critics” as to what great art is. Statements like this contribute to the elitism that plagues “high art” and keeps wider audiences out.

To further support the need for a spectrum of voices, it is important to acknowledge that there is a high-level discourse carrying on in places such as ArtForum[32] where critical conversation within the field feeds the maturation of the field itself. The need to silence the voice of audiences that may be validating their own involvement in the performing arts seems counterintuitive. It bears the question of who the work is being made for–the many or the few?–or, as is probably the general case, both. The conversation around who is qualified to critique art simply appears to be the old guard confronting the ways of the new guard and makes me think of the morbid but beautiful political adage, “in death there is hope.”

Salon du Garage

For me, these arenas of audience participation are microcosms of society at large. As technology and connectivity have blurred distinctions between amateur and professional, relations between inclusiveness and exclusiveness and audience and artist have become difficult to discern. Society is in a constant state of making sense of the new while maintaining what it can of the old. My current art-making process addresses this blur head-on. As an outgrowth of my graduate studies, I have created a series of performances that I call Salon du Garage[33] that center on four overarching topics of inquiry: performance in non-traditional spaces, letting the reality behind the performance show as content, choreographic intervention by audience participation and, making art without subsidy. As described on my website: Salon du Garage is an ongoing platform for work. Having performed in the grand spaces of German opera houses, festivals in Monaco, and New York City theaters, I, Dawn Stoppiello, now present intimate performance installations in my garage.

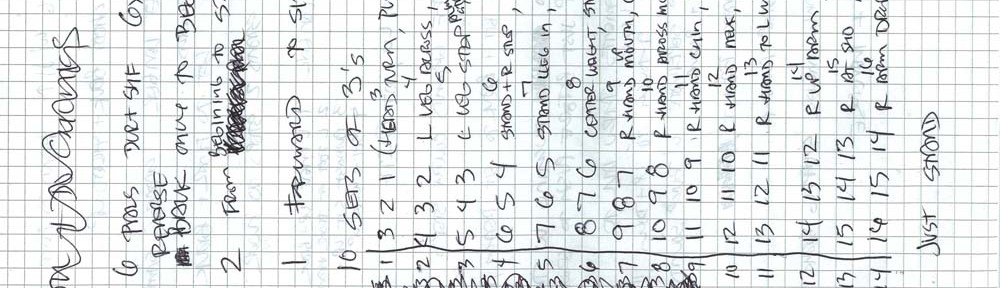

A garage is a space where things get worked on. As a method of working on myself as a solo artist through group council, my audiences and I together play out structured improvisational movement scores that are both silly and serious. The decision to make the garage a performance site stems from necessity and creativity: my own personal art subsidy, in the form of income and then alimony provided by my primary collaborator (and former husband), is drying up, so I have been exploring the idea of making art as an “amateur,” with no money to fund it and asking for no money to experience it. On every Saturday in April of 2013, I performed a structured improvised solo in my garage for 20 or fewer audience members who were asked to participate in various ways. These decisions were inspired by a personal shift in how I perceive both the value and participation of audiences in my own performance work.

As part of the Salon du Garage, I asked audience participants to complete a simple survey about their experiences. While not in-depth scientific research, the results[34] did provide me with the feedback I was hoping for; evidence that audiences want an intimate, creative, thoughtful experience, even if they are not “formally” trained or involved with dance and performance directly. In essence, the experience for the audience in my garage felt safe, inclusive, exciting, personal, and unpretentious. My goals have been fulfilled.

Conclusion

Here in 2013, we are in a post-post-post-modern age of performance that doesn’t even have a singular moniker.[35] It seems as if everything goes. There are endless genre names within performance, abundant methods of making performance, near total acceptance of non-traditional venues, untold ways to “engage” audience, and perpetual new methods for raising money. There is no more “edge,” no more “avant-garde,” and no more “outsider.” If you are an outsider then this automatically makes you an insider somewhere else. In this overly connected moment, the difference between reality and performance is hard to perceive. Guy Debord perhaps had no idea of the extent to which his ideas would be verified when he wrote, “The spectacle, grasped in its totality, is both the result and the project of the existing mode of production.”[36] This could pertain to the way audiences are connected to the construction and observation of performance and art in general. If the “existing mode of production” is the Internet with its portals for involvement in real and virtual expression, the computer as a site for making, witnessing, supporting, commenting, all of the audience roles described above, then the process is the product.

Debord continues, “The social practice which the autonomous spectacle confronts is also the real totality which contains the spectacle[37].” He is explaining that the reality of performance is also the fantasy of performance and the construction of the spectacle is also the spectacle. Reality is performance and audience is performer. Debord may have never envisioned performances happening in a Portland garage incorporating these modes of perception and participation, but in my creative incubator, I have found satisfying ways of fostering connection. The direct participation of an audience and exposing this audience to both the reality of the performance space and the reality contained within the performance came as a reaction to feeling disconnected from any real-world relevance in my performance work.

In some ways, it took my own dislocation from known methods of making and presenting performances to uncover these concepts that now lie at the crux of my work. The intense focus of graduate school, relocating from New York City back to Portland, Oregon, and wanting more fluid performer-audience relations, all of these mark different modes of engaging with my surroundings and art making. As I am rethinking how to serve an audience, I am drawn to freeing audiences, allowing them to be more included in my process and performances. My shift comes directly from having seen so many performances where I felt disconnected and wanted to make the performance more “real” and relevant to as broad a range of people as I can. I even envision having fun as something more appealing than suffering or serving up content that is so conceptual that only an elite audience could appreciate it. I am not stating that it is necessary to place one over the other, garage or elite, but I want to toggle between the two places. I want my two avenues of art production to reflect my desire for an audience that is closer to, if not inside of, the act of performance.

To conclude with the initial inquiry, “Who is my audience?” Everyone who has the inkling to take a risk to be creative, think, and play games, or anyone willing to show up. What do I want from them? My first answer is the honest and embarrassing adolescent sentiment, “all I want is for them to like me”. At my most universally human core is the desire to love and be loved; my offering of performance is one way of communicating this aspiration. Closer to the surface is my hunger for audiences to drive me to take creative risks, to think and act with rigor, to motivate my artistic growth, to witness my existence. What do they want from me? They want me to be courageous and play out the serious and the silly aspects of life that we all share. They want me to be a reflection of them. My audience is me. The audience is everything and so am I.

Footnotes

[1] I would describe traditional to mean organizing as a non-profit, applying for government and foundation grants, working with an agent, having an annual fundraising event, attending conferences and performing at established venues.

[2] http://troikaranch.org/

[3] Performance Art: The Futurists to Today by Roselee Goldberg

[4] http://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=ron+athey&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_n’_Tina’s_Wedding

[6] http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/965

[7] http://www.gobsquad.com/about-us

[8] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EX1smbRYzpo

[9] http://www.webfoundation.org/vision/history-of-the-web/

[10] http://www.mitchellrose.com/globetrot/

[11] Quote from Ella Baff, Director Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival “People are drawn to the arts because of personal relationships, not physical structures”, Entering Cultural Communities by Gram and Farrell, pg. 50

[12] http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/profession

[13] http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/amateur?show=0&t=1367178696

[14] http://www.salon.com/2011/04/26/10_year_time_capsule_writers_strike/

[15] “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes”. As quoted by Andy Warhol in 1968.

[16] http://www.mortonsubotnick.com/

[17] Douglas Sonntag, Dance Director, “National Endowment for the Arts: A History, 1965-2008,” pages 170-183

[18] Source: http://www.nea.gov/research/notes/74.pdf

[19] http://www.arts.gov/about/Budget/AppropriationsHistory.html

[20] Grantmakers in the Arts, GIA Reader Vol. 21, Fall 2010

[21] National Endowment for the Arts report 2007

[22] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crowd_funding#History_2

[23] Washington, DC-based dance artist and community organizer, Ilana Silverstein in conversation with the writer.

[24] http://pndblog.typepad.com/pndblog/2012/10/funding-for-the-arts-month-arts-and-community-engagement.html

[25] http://webmarketingtoday.com/articles/viral-principles/

[26] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_blogging

[27] http://www.hiphoppress.com/2006/09/village_voice_f

[28] http://www.danceinsider.com/

[29] http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1994/12/26/1994_12_26_054_TNY_CARDS_000369157

[30] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-kaiser/the-death-of-criticism-or_b_1092125.html

[31] http://www.culturebot.org/2013/03/16197/re-cap-of-everyones-a-critic-on-the-boards-in-seattle/

[32] http://artforum.com/

[33] see Salon du Garage page

[34] Salon du Garage survey, no longer available

[35] Stoppiello, Dawn. What to Call it and Why December 2012

[36] Society of the Spectacle, Separation Perfected #6, Black & Red, Detriot, Reprinted in 1983

[37] Society of the Spectacle, Separation Perfected #7, Black & Red, Detriot, Reprinted in 1983